ICE Stealthily Acquires Warehouses for Detention Centers, Ignoring Local Officials

In a Texas town bordering the Rio Grande, whispers of federal immigration plans began circulating as officials learned that three massive warehouses were set to be converted into a detention center. The Department of Homeland Security had already finalized a staggering $122.8 million deal for the 826,000-square-foot facilities in Socorro, a community of 40,000 just outside El Paso.

“No one from the federal government reached out to inform us about what was happening,” lamented Rudy Cruz Jr., the mayor of Socorro, a predominantly Hispanic area characterized by ranch homes and trailer parks interspersed with strip malls and distribution centers.

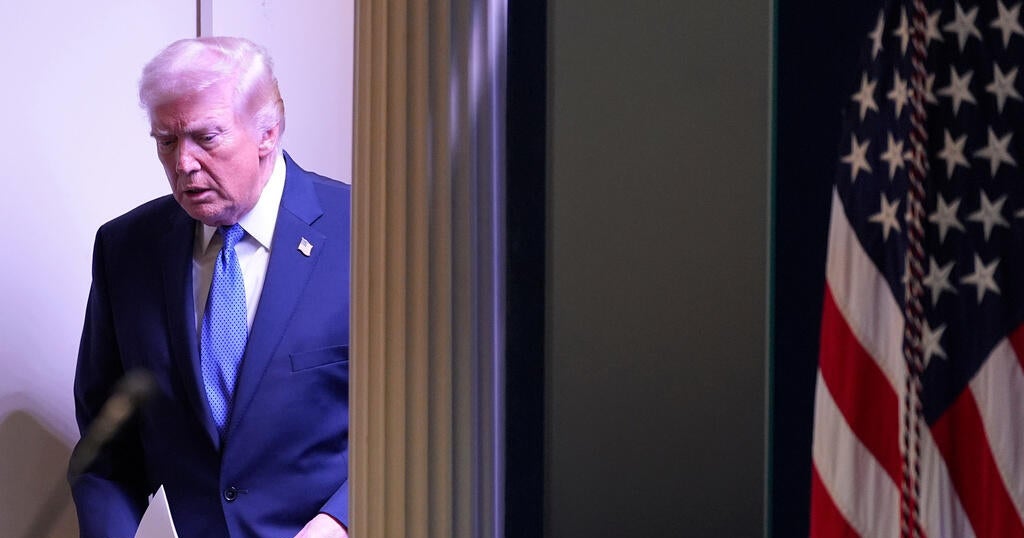

Socorro is not alone; at least 20 other U.S. communities with large warehouses have become targets for Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s (ICE) ambitious $45 billion expansion of detention facilities. As public support for ICE and the Trump administration's immigration policies wanes, local leaders are voicing their objections to mass detentions, fearing that these facilities will strain local resources and diminish tax revenues.

“I feel,” Cruz expressed, “that they operate in silence to avoid opposition.”

ICE has acquired at least seven warehouses across states including Arizona, Georgia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Texas, according to official deeds. While some deals have been announced, others remain pending, and eight potential sales have been abandoned.

In a statement, DHS refrained from labeling the sites as mere warehouses, insisting they would be “well-structured detention facilities” adhering to established standards. However, the process has been fraught with confusion; ICE recently admitted to a “mistake” regarding warehouse purchases in Chester, New York, and Roxbury, New Jersey.

While DHS has confirmed its search for additional detention space, it has not disclosed specific locations prior to acquisitions. Some cities learned of ICE's intentions through media reports or from an activist-shared spreadsheet whose origins remain unclear.

The full extent of the warehouse project became evident on February 13 when New Hampshire's governor's office released an ICE document revealing plans to invest $38.3 billion to increase detention capacity to 92,000 beds. Since the Trump administration took office, ICE's detainee numbers have surged from 40,000 to 75,000 across more than 225 sites.

These warehouses could serve as consolidation points to enhance capacity. Plans include eight large-scale detention centers capable of housing between 7,000 and 10,000 detainees each, along with 16 smaller regional processing centers and the acquisition of ten existing “turnkey” facilities.

This initiative is financed through a significant tax and spending bill passed by Congress last year that nearly doubled DHS's budget. The Trump administration is utilizing military contracts for construction, which allows for expedited processes shrouded in secrecy, according to Charles Tiefer, a law professor at the University of Baltimore.

The Socorro warehouses are so expansive that they could accommodate four and a half Walmart Supercenters, starkly contrasting with the town's historical Spanish colonial architecture. At a recent City Council meeting, public comments lasted for hours. “Innocent people are getting caught in their dragnet,” voiced Jorge Mendoza, an El Paso County retiree whose family has deep roots in Mexico.

Concerns about recent deaths at an ICE facility near Fort Bliss were echoed by many speakers.

Even communities that previously supported Trump are taken aback by ICE's plans. In Berks County, Pennsylvania, Commissioner Christian Leinbach reached out to local officials upon hearing rumors of an ICE acquisition in Upper Bern Township. To his surprise, he later discovered that ICE had purchased the building—marketed as a “state-of-the-art logistics center”—for $87.4 million without any prior notice.

“There was absolutely no warning,” Leinbach stated during a meeting where he highlighted potential losses exceeding $800,000 in local tax revenue due to the federal facility. While ICE promotes the income taxes its employees would contribute, the facilities themselves will be exempt from property taxes.

In Social Circle, Georgia—a city that also strongly backed Trump—officials were blindsided by plans for a facility capable of housing between 7,500 and 10,000 detainees. The city learned about the $128.6 million purchase of a one-million-square-foot warehouse only after it was finalized. Local leaders expressed concerns about whether their infrastructure could support such a facility.

ICE claims it conducted due diligence to ensure that local utilities would not be overwhelmed; however, Social Circle pointed out that the agency's analysis relied on a yet-to-be-constructed sewage treatment plant.

“The City has repeatedly communicated that it does not have the capacity or resources to accommodate this demand,” officials stated.

In Surprise, Arizona, officials sent a stern letter to Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem after ICE purchased a large warehouse in a residential area without warning. Arizona Attorney General Kris Mayes suggested potential legal action to declare the site a public nuisance.

Back in Socorro, residents waiting to voice their opposition spilled out of City Council chambers, standing beside murals honoring the Braceros Program that once bolstered the local economy before mass deportations began in the 1950s under President Eisenhower.

Eduardo Castillo, a former attorney for the U.S. Department of Justice, encouraged city officials to challenge the federal government despite its intimidating nature. “If you don’t at least try,” he warned, “you will end up with another inhumane detention facility built in your jurisdiction.”